Memories of Hestercombe – Part 13: The Lost Kitchen Garden

The Hestercombe archives are bursting at the seams with facts, pictures and accounts of the history of Hestercombe and those who lived and worked here. In this instalment of Memories of Hestercombe, we explore the history of the now lost kitchen garden from the time of Sir Francis Warre onwards.

Written by Kim Legate, Senior Archivist

Sir Francis Warre: 1659-1718

The household accounts for the early 18th century indicate that Sir Francis Warre (1659-1718) and his family benefited from a surprisingly varied diet of fruit and vegetables. The former included Mazzard cherries, walnuts, apples, pears, figs, and melons; the latter broad beans, peas, carrots, corn, radishes, leeks, onions, savoy cabbage, potatoes and spinach. Thought to have been introduced by the Huguenots, the small disease resistant mazzard appears to have been grown at Hestercombe from an early date. By 1707 a ‘cherry court’ was in existence, by 1715 Sir Francis Warre was planting more cherry trees — ‘To him for Mr Silvers man that brought the cherry trees’ (00-02-06) — and by 1838 a field on the estate had been named the ‘Cherry Grove’ (today the lower car park). However, the majority of Sir Francis Warre’s fruit and vegetables appear to have been cultivated in a large partially walled-in kitchen garden that still survives to the southwest of Hestercombe House. Most likely 17th century in date, this garden was maintained in Sir Francis’s day by ‘John the [Head] Gardner’ and a staff of nine ‘Weeders’ that included Bess Rossetter, Old Watford, Joan Ball, Goody Waford, Old Standfast, Boon, Duke, Hoskens and a Garden Boy. Thomas Godfrey of Westminster, London, gardener, supplied many of the trees and seeds.

The old kitchen garden was gradually improved. In December of 1703 Sir Francis Warre paid John Noble 1 pound 10 shillings ‘towards the garden Walle’; on 25 June 1709 he gave Denish two shillings six pence ‘for four days Work raising stones for the wall’ (rubble stone from the East Combe quarry?); and in August 1709 he reimbursed stone mason John Jordan 6 pounds 10 shillings 3 pence ‘for the Garden Wall for his worke about the Mill pond and for the Wall by the orchard gate & for worke about my Wifes clossett [closet] & for the oven at the parsonage’. WHEW! Not to be forgotten, Mr. Humphry was given 1 pound 4 shillings by Sir Francis ‘for Making and putting up the Balls on the garden gate’ on 25 August 1711 and the estate bricklayer was paid twelve shillings six pence ‘for his work in the garden & over the little sellere [cellar] in the parlour’ on 5 June 1717. (The medieval solar that adjoined the south side of the Great Hall was refitted as the Warre dining room in late 1717.)

Fig. 1 Hestercombe House, 1700

Tropical fruit (particularly lemons and oranges) was also a component of the Warre diet and from the 1680s tender and potted plants were overwintered in an Orangery, today the Bampfylde Hall, constructed just west of Hestercombe House (Fig. 1). Incorporating the arms of Sir Francis Warre’s first wife, Anne Cuffe (1660-90) of Creech St. Michael this building may have been a political statement in support of William of Orange who landed at Torbay in 1688, the start of the Glorious Revolution

Fig. 2a Colonel Dansey’s c. 1788 plan, ‘Hestercombe Lawn’

Fig. 2b – Detail of ‘Hestercombe Lawn’ c. 1788

The earliest plan view that we have of the Hestercombe kitchen garden and its environs is dated 1788 (Fig. 2). ‘Hestercombe Lawn’ was drawn by Lieutenant Colonel William Collins Dansey (1744-93), a friend of Coplestone Warre Bampfylde, and member of the gentry from Brinsop, Hertfordshire, who served with distinction with the 33rd Regiment of Foot in the American revolutionary war and was appointed ADC (Aide-De-Camp) to George III. The estate kitchen garden is clearly indicated in the bottom left hand corner of the plan, sitting enclosed on three sides by walls and roughly organized into four quadrants, each encircled by a single line of small, most probably fruit trees. A continuous border runs along the inside of the three walls and there is a roughly rectangular fenced enclosure to the immediate north, apparently containing more dwarf fruit trees. Further to the north near the top of Colonel Dansey’s plan is Sir Francis Warre’s Orangery with a row of trees growing in front of it, suggesting that the now shaded building is no longer being used to house tender plants.

Fig. 3 – Miss Warre’s 1839 estate plan

An ink and watercolour plan produced for Miss E. M. T. Warre in 1839 (Fig. 3) reveals a kitchen garden complex much changed from Lieutenant Colonel Dansey’s day. Three outbuildings have been added and the walled-in section is now divided into three compartments that together cover just over 2 acres: from north to south the Higher Garden (#60 – 0.34 ac.), Middle Garden (#61 – 0.31 ac.), and Lower Garden (#62 – 1.53 ac.). Two of the outbuildings abut the west wall, with the northernmost and largest occupying the site of the still extant (albeit with a modern extension) Gardener’s Bothy. The more substantial south-facing structure that straddles the Middle and Lower Gardens is almost certainly the greenhouse named in the estate inventory prepared in May 1819 by John Robins of London following the death of Miss Warres’ father, John Tyndale Warre. A list of the building’s contents (below) indicates that J. T. Warre maintained tender plants inside, in particular orange trees and aloes, but the inventory also mentions a ‘Mellon Ground’ with cold frames that must have existed nearby, perhaps in the Middle Garden, also a ‘Tool-House’ that could conceivably be the southernmost building shown next the west wall. To the west of the walled garden is a field for growing potatoes (#64) along with a recently dug pond (#65) and a shrubbery belt to screen off the garden’s fruit and vegetables from Hestercombe House and shield them from chilling northerly winds (#63).

Garden, Tool-House etc

Two wheel Barrows

An old Iron Boiler

Two wire Sieves

4 Watering pots – a Gravel Screen

Dust Bin & 2 Stools

6 Iron Rakes

A Mattock 2 pick Axes

3 Potatoe forks 5 Spades

A Dutch Hoe & 5 Others

A Rummer & 4 Dibbers

A Cupboard & 4 Vegetable Baskets

reel & line 2 Pr Sheers

Hatchet a Saw Pr Bellows

Two Sieves a Hammer

Two Nests of Seed Drawers

A Gun

Two Chairs a Table

A Syringe – a Garden Engine

A Quantity of old Netting

Mats & a Shovel

Sundry Garden pots & pans

9 Large Do for Cale & pans

Three Scythes

A pair of Steps

A Grindstone & frame

A Dung fork

A Dung Drag

Mellon Ground

A 3 Light frame & lights

Two 2 light Do – old

A one light Do

15 Hand Glasses in lead work

An old frame two planks etc

Green House

5 Tier of Stages

7 Orange etc Trees in Tubs

9 Do in Pots

About 180 Green House plants in pots

Two Aloes

An Iron Roller & frame

A Stone roller Iron frame

From: Inventory of Hestercombe House (including books, pictures, plate, and outbuildings, prepared by John Robins of London 1819 {SHC DD/GC/2}

Fig. 4 – First Edition OS Map 1887

Edward Berkeley Portman (1st Viscount Portman, 1799-1888)

In 1872 Edward Berkeley Portman (1799-1888), 1st Viscount Portman purchased Hestercombe, following the death of Miss E. M. T. Warre in April and set about remodelling the House and introducing improvements to the wider estate. By 1887 (when the 1st Edition Ordnance Survey was compiled) (Fig. 4) the latter included an additional glasshouse and ancillary building (boiler house?) in the northwest corner of the walled garden complex along with a roofed structure adjoining the north wall of the Bothy and a fourth construction abutting the old outbuilding (J. T. Warre’s Tool-House?) to the south. It is highly unlikely that Miss Warre had commissioned the new glasshouse. ‘Careful in the extreme’, she is not known to have made any significant outlays at Hestercombe after inheriting the debt ridden estate from her father in 1819. However, Miss Warre, who had let the kitchen garden compound to tenant farmer, John Bird, by 1839, does appear to have made some modest improvements to the area during her lifetime and these would seem to explain the other two new builds. The sale particulars of 1872, compiled by Messrs Beadel, estate agents, mention a pottery shed and potato house in addition to the greenhouse (a ‘small conservatory’ was their term) and the tool house established by John Tyndale Warre.

Testimonial. Hestercombe, Taunton.

“Gentleman – I am very pleased indeed with the Range, and the way your workmen have done their work. Yours faithfully, (Signed) A. J. Keen”. (Boulton & Paul Catalogue [March 1895])

Fig. 5 – Boulton & Paul Glasshouses at Hestercombe

Fig. 6 – Boulton & Paul range with strawberry patch foreground 1904

Fig. 7 – Kitchen Garden, looking north along main axis 1904

The kitchen garden complex was enlarged and modernized yet again by the 1st Viscount Portman’s grandson, E. W. B. (‘Teddy’) Portman who added an extensive range of modern coal-fired glasshouses and a fourth walled-in garden designed by Edwin Lutyens on the site of Miss E. M. T. Warre’s former potato plot. The new hothouses were erected against the north wall of the Lower Garden by Boulton & Paul Manufacturers, Rose Lane Works, Norwich, in 1895, barely a year after Teddy and Constance Portman had taken up permanent residence at Hestercombe. Such was the magnitude of the project that the company’s catalogue for 1895 featured a full elevation drawing of the ‘Range of Horticultural Buildings recently erected at Hestercombe, Taunton, for The Hon. E. W. Berkeley Portman’ along with an effusive endorsement of the buildings by Teddy’s Head Gardener, A. J. Keen: ‘GENTLEMEN – I am very pleased indeed with the Range, and the way your workmen have done their work.’ (Figs. 5-7) The 3rd Edition Ordnance Survey, surveyed 1912-13 (Fig. 8), illustrated the remainder of Teddy Portman’s kitchen garden improvements. The amalgam of outbuildings that were added to the Middle Garden to support the new range of Bolton & Paul glasshouses to the south included potting sheds, a boiler house and a cold frame yard. Further to the west, a new apple orchard was planted between the Orangery Lawn, formerly Thistle Close, and the larger of the two fish ponds that crossed the southern parkland. (In recent years the Portman Orchard has been replanted twice in 1990-95 and 2012, in both instances using varieties available before 1900.) The row of cherry plumb trees in evidence below the apple orchard and along the north side of the road leading to West Monkton, then ‘Hestercombe Road’, dates to about 1903.

In a 1980 interview with The Somerset County Gazette, former Head Gardener, Andy Thomas, who worked at Hestercombe for Mrs. Portman 1926-51, enthused about the bounty once generated by kitchen garden: ‘. . . we grew everything in the greenhouses — melons, grapes, peaches, carnations, stove plants, gardenias – the lot’. He also remembered that two horses were kept to convey vegetables to the kitchen and that Mrs. Portman frequently took hampers of fruit and vegetables from the walled-in gardens to the Taunton and Somerset Hospital at East Reach. Back at Hestercombe, she observed an exacting daily routine that began with a visit to the dairy (between 11 and 12), after which she went directly to the kitchen garden and rang the bell for the Head Gardener. While in the glasshouses she inspected the various pot plants, orchids, carnations, amaryllis, lilies, chrysanthemums, cinerarias, ferns, freesias, and cyclamen amongst others. And then there was that Ball.

The Hestercombe Grand Ball

“The floral decorations were carried out by A. J. Keen, head gardener, with much assistance from the foreman, W. Cooper. So much beauty reflects the highest credit, especially considering the short time occasioned in the erection of the conservatories and the bringing of numerous plants to such perfection.” (‘A Hestercombe Soiree’, Somerset County Gazette, January 1897)

In January of 1897 ‘one of the most brilliant gatherings that has ever taken place in Somerset’ took place at Hestercombe House to celebrate the introduction of electric lighting on the property. A 6 HP (4.41 kW) hydroelectric turbine recently installed in the Dynamo House adjoining the mill by F. M. Newton’s Ltd. Electrical Engineers of Taunton, allowed 200 invited guests to dance until 4:00 am, with suitable pauses to relax and take refreshment in rooms lavishly decorated for the occasion with flowers grown in the recently erected Boulton & Paul glasshouses — or ‘conservatories’ as the Gazette reporter preferred to call them. Many were of the tropical persuasion. A great bank of fragrant white narcissus hovered over the dining room fireplace and clouds of arum lilies, freesias, orchids, lilac, poinsettia, and violets drifted through the Column Room in a veritable festival of scent and colour. Read more about the Grand Ball of January 1897.

Fig. 8 – Third Edition OS Map 1912-13

Fig. 9 — Second Edition OS Map 1903

Given the scale and complexity of the new flower garden that Edwin Lutyens designed for the Portmans in the decade that followed, his extension to the walled-in kitchen garden was probably completed after the construction of the former which took place 1904-1908. (Moreover, the extension appears on the 25 inch Ordnance Survey Map for 1912-13 [Fig. 8] but not on the 1903 version [Fig. 9]).

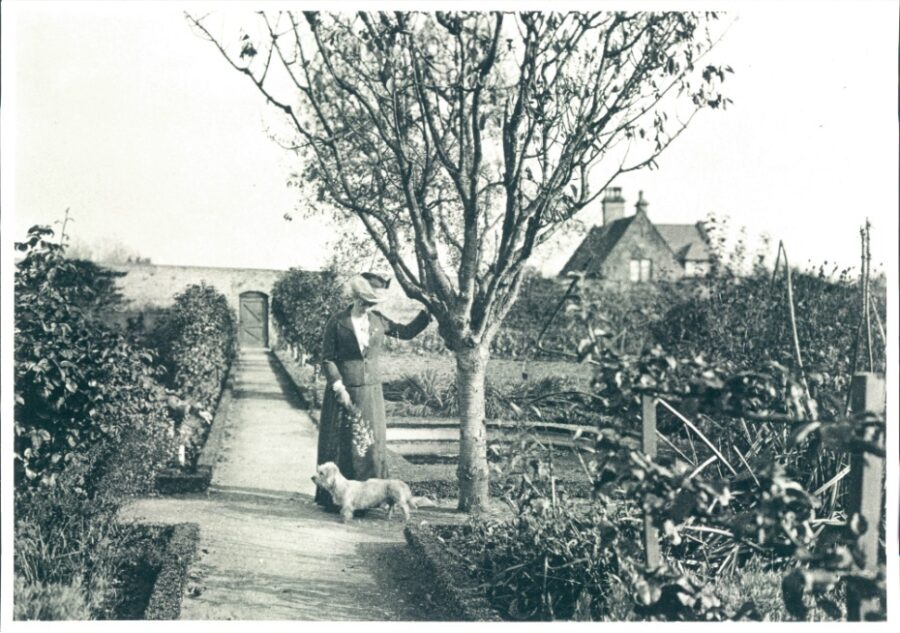

Fig. 10 – Edwin Lutyens walled garden extension, 1927

Photographed by Country Life Magazine in 1927 (Fig. 10), the new fruit and vegetable enclosure was located in the angle of Hestercombe Road and the main kitchen garden or Lower Garden, with a ha-ha separating it from the parkland to the west. The interior was bisected by a north-south running stream (fed by the small pond to the north), with footbridges of coursed local stone traversing it at both ends and fruit trees trained as espaliers, fans or cordons covering the walls. Strips of lawn ran alongside the stream in a zigzag pattern flanked by low stone retaining walls that incorporated steps, leading up to, and through, herbaceous borders and vegetable plots. The new kitchen garden covered a total area of 0.52 hectares (1.28 acres) as compared to the 0.78-hectare (1.92-acre) extent of its larger counterpart to the east. Together with the two smaller walled-in enclosures to the north, the entire kitchen garden complex now comprised 1.51 hectares (3.71 acres) of land. Edwin Lutyens had successfully incorporated walled-in gardens into his design commissions before, as at Greywalls, East Lothian (1901), Whalton Manor, Northumberland (1908), Great Maytham Hall, Kent (1909) and Lindisfarne, Northumberland (1911) but with the exception of Lindisfarne and Hestercombe the emphasis of these enclosures was on ornamental horticulture rather than fruit and vegetable production.

Fig. 11 – W. C. Burn, General Foreman Walled Gardens, & Under Gardeners c. 1907

General Foreman, Walter Charles Burn (b. 1878) of 1 Park Gate (Fig. 11), was among the gardeners who worked in the kitchen garden complex at this time. Burn was employed on the estate 1902-07 under the able direction of Mr. Albert Hubbard, ‘late Foreman at Blenheim Palace Gardens’, who had relieved A. J. Keen in October 1902. An ardent cricketer, the amiable Hampshire native (Hursley) had previously been employed to the full satisfaction of Head Gardeners at Gaunts House, Dorset; Rhode Hill, Lyme Regis; and Buckminster Park, Lincolnshire. He lived first in the five-room Gardener’s Bothy (Fig. 12), by now the ‘Gardener’s Lodge’, then at 1 Park Gate where he settled down with his new wife, Martha, in 1905. Their first child, Rosa Fanny, was, like so many of the children born on the estate, baptized at St. Mary’s Church Hestercombe, on 1 December 1907 by chaplain, W. R. Rainey. Burn and Hubbard got on well and when it came time for the General Foreman to move on Hubbard did not hesitate to provide him with a first-rate letter of reference (see below).

Fig. 12 – The Gardener’s Bothy 1968

The Gardens, Hestercombe, Taunton

May 24th 1907

. . . I can confidently recommend him [Walter Burn] to anyone as a thorough, honest, sober, and industrious man. He is well up in all branches appertaining to a well kept garden & a good manager of men. He leaves here to better himself & has my heartiest wishes for future success.

A. Hubbard

gardener to The Honble E. W. B. Portman,

Hestercombe, Taunton

Fig. 13 – Kitchen Garden, view east 1904

By 1911 the 45-year-old Hubbard was supervising a staff of at least ten gardeners, including two ‘Garden Lads’: Jack Roy, aged 17, and James Cording, aged 15 lived with their families in Upper Cheddon. Henry Britton (28), Charles York (26), Charles Jones (25), Frank Juson (22), John Wadham (19) and Charles Dyer (19) were all single and lived in the Gardener’s Lodge. William Tucker (22) resided at Park Gate with his uncle, Henry Tucker, the caretaker of the Reading Room and Albert Shaw (31) occupied a ‘tied house’ (estate cottage) opposite Cheddon Fitzpaine church. Albert Hubbard lived with his wife, Florence, their two sons, Albert and Harold, and his mother-in-law, Kezia Mitchell, in the seven-room Gardener’s Cottage (c. 1896) (Fig. 13) that still stands just east of the kitchen garden. It has since been renamed ‘Kirklands’ in honour of John Kirkland, Hestercombe Head Gardener c.1926-1951.

Fig. 14 – Harry Nutting (standing middle) and Albert Curry (seated right) with colleagues by Gardener’s Bothy c.1914

Fig. 15 – Hestercombe Gardens & Grounds Staff, April 1914. Harry Nutting is seated front row, 3rd from left, next to Head Gardener John Ernest Arnold.

The majority of Hubbard’s staff were employed in the walled gardens. By February 1912 Harry Nutting (1884-1983) was among them, having arrived at Hestercombe from Hesley Hall, Thorpe Hesley, South Yorkshire at around the same time as Albert Curry, who was put to work in the Bolton & Paul greenhouses. The two men were photographed together with colleagues near the kitchen garden on more than one occasion as well as appearing in that memorable snapshot ‘Hestercombe House, Gardens and Grounds Staff, April 1914’ (Figs. 14-15). Harry Nutting worked on the estate until 1915, when he enlisted in the British army, and then again after the war from 1919 until the spring of 1921. Wounded in action twice Harry struggled to overcome the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on his return to civilian life and for many years thereafter grappled with a recurring nightmare of the trenches falling in on him. While working at Hestercombe, Harry met Susan Stagg, the middle of five sisters who had gone into service immediately after leaving school in her home village of Montacute, Somerset. By 1911 Susan had risen to the post of First Housemaid to Mrs. Portman, one of twenty-one servants then employed in the House and the supervisor of three Under Housemaids: Emily Child, aged 24; Rose Marsh, 21; and Dorothy Colbourne, 19. When Susan and Harry married in 1920, Mrs. Portman was present, having already given them a fine Victorian oak corner chair as a wedding gift. She later paid for a midwife to assist with the birth of Susan and Harry’s daughter, Margaret (b. 1920), and when the young couple decided to move on in 1921, she furnished them with a letter of reference that left no doubt as to their reliability and good character (though in handwriting of exceedingly aristocratic illegibility). (Fig. 16)

Fig. 16 – Letter of reference by Mrs. Portman for Harry & Susan Nutting, 30 May 1921

Fig. 16 – Letter of reference by Mrs. Portman for Harry & Susan Nutting, 30 May 1921

Hestercombe,

Taunton.May 30

Sir,

I beg to recommend Mr. & Mrs. H. Nutting as competent caretakers.

He has worked in my Gardens for 9 Years, with a War absence of 4 Years

& his wife lived with me as Housemaid for 10 Years (only leaving me, to be married:) they are a very respectable Couple, & I feel sure Would Give every

satisfaction. I will gladly answer any questions con-cerning them.Yrs. Faithfully

Constance Portman

(the Honble Mrs)

The Crown Estates (1951)

Harry Nutting’s long and successful career as a freelance gardener ended in 1948 at Penstowe near Bude, Cornwall. He had been retired for only three years when, following the death of the Honble. Mrs. Portman in May 1951, the Hestercombe Estate was taken over by the Crown Estates. (In December 1944, the entire Portman Somerset Estate, comprising 10,488 acres [4,244 hectares] in 20 parishes had been conveyed to the Commissioners of Crown lands to offset death duties levied on the family.) Correspondence from Crown Receiver, H. A. Sawyer, to the Secretary, Office of Commissioners of Crown Lands, dated 11 July 1951 and bearing the heading ‘Hestercombe. Future Policy and Re-letting’, commented at length on the money-making potential of the kitchen garden, which was no longer in full use.

‘The walled garden and glasshouses. Whatever the outcome and treatment of the mansion house, whether separately or comprehensively with the whole, the garden must essentially be maintained in no less state than they are at present and this frankly is not much more than 50%, if that. Five [out of seven] gardeners are employed there at the moment. I feel, therefore, that on take over by the Commissioners the gardens, with the garden staff, should be taken over also and run under direct management pending decision as to subsequent letting. The present practice is to run these commercially sending the produce into town and this has been done for very many years. I have not seen the books accounting for this enterprise but it could be a commercial proposition’. (PRO Crest 35/1152 58985)

The following year, a ‘Rating and Valuation of Hestercombe Estate’ undertaken for the Commissioners of Crown Lands spelled out a change of heart, however, and both walled gardens inclusive of the gardener’s Bothy and the late head gardener’s house, ‘Kirklands’ were let. In March of 1952 newly married local man, Mr. Alan Richards, moved into the Bothy which at that time had three rooms on the ground floor (kitchen, bathroom, sitting room) and two rooms, both bedrooms, on the first floor, but still lacked electricity. Richards then set about converting the walled gardens to a market garden, hiring two of Mrs. Portman’s former gardeners for the enterprise: Ernest C. Farr who was approaching 60 and living at 2 Park Gate, and H. Vaughan who was based in the Groom’s Cottage on the west side of the Hestercombe stable block, today the Gift Shop. Chrysanthemums, apples, pears, plumbs, nectarines, peaches, roses and black homburg grapes (centre glasshouse or ‘vine house’) were grown, with all the grapes being sold to local greengrocer, Collard’s of Station Road, Taunton. (English grown grapes were still a rarity in the 1950s.) In a December 2007 interview, Richards recalled that the walled gardens were intact, albeit overgrown, when he took possession of them in 1952 and that the potting sheds and glasshouses (with their coal-fired boilers!) were still in good working order.

Fig. 17 – Derelict footbridge with round & square piers, Lutyens walled garden 1998

Fig. 18 – Dilapidated footbridge, Lutyens walled garden 1998

In 1961 the Hestercombe dairy and 91 acres of southern parkland were leased to John Raymond Dill, a local farmer. In subsequent years the larger of the two stone-edged fishponds were infilled by Dill (1966-67) and Sir Edwin Lutyens’ walled garden extension, purchased outright by his son, John, in 1991 along with the remainder of the kitchen garden, was stripped of its interior furnishings to make way for a commercial plant nursery. Lost were several of the key garden design elements that Lutyens had borrowed from the Formal Garden, most notably the round and square piers that ran the length of the Pergola in alternating sequence. Modified in the kitchen garden to incorporate chains for the training of roses as garlands, they bore clear witness to Jekyll’s influence over her longtime architect friend. (Figures 17-19).

Fig. 19 – Doorway & missing wall section, Lutyens walled garden 1998

A modification of the continuous pergola is in many cases as good as, or even better than, the more complete kind. This is the series of posts and beams without any connection in the direction of the length of the path, making a succession of flowering arches; either standing quite clear or only connected by garlands swinging from one pair of piers to the next along the sides of the path, and perhaps light horizontal rails also running length-wise from pier to pier. This is the best arrangement for Roses, as they have plenty of air and light, and can be more conveniently trained as pillars and arche . . . (G. Jekyll, ‘The Pergola in English gardens’, The Garden 62 (1902), p. 326.

Find out more

Find out more about Hestercombe’s history, or pay us a visit and explore our estate.

List of Illustrations

Figure 1: — ‘Hestercombe House 1700’, with Sir Francis Warre’s Orangery bottom left.

Figure 2a: — Colonel Dansey’s c. 1788 plan, ‘Hestercombe Lawn’.

Figure 2b: — Detail of ‘Hestercombe Lawn’ c.1788, showing the Kitchen Garden.

Figure 3: — Kitchen Garden from 1839 estate plan drawn for Miss E. M. T. Warre.

Figure 4: — Kitchen Garden from 1st Edition Ordnance Survey Map, surveyed 1887.

Figure 5: — Glasshouses built at Hestercombe by Boulton & Paul, Norwich, March 1895.

Figure 6: – Section of the Boulton & Paul range with field of strawberries foreground 1904.

Figure 7: — Looking north along the main axis of the Kitchen Garden to the Boulton & Paul glasshouses 1904.

Figure 8: – Kitchen Garden from 3rd Edition Ordnance Map, surveyed 1912-13.

Figure 9: — Kitchen Garden from 2nd Edition Ordnance Survey Map, surveyed 1903.

Figure 10: — Edwin Lutyens’ walled garden as photographed by Country Life 1927.

Figure 11: — Walter Charles Burn, General Foreman walled gardens (seated right) with under gardeners c. 1907.

Figure 12: – The Gardener’s Bothy 1968.

Figure 13: — The Kitchen Garden 1904, view east with the Head Gardener’s cottage, ‘Kirklands’, visible background.

Figure 14: — Harry Nutting (standing middle) and Albert Curry (seated right) with colleagues by the Gardener’s Bothy c. 1914.

Figure 15: — Hestercombe Gardens and Grounds Staff April 1914. Harry Nutting is seated in the front row, 3rd from left, next to Head Gardener, John Ernest Arnold.

Figure 16: — Derelict footbridge in Lutyens’ walled garden decorated with round and square piers 1998.

Figure 17: — One of two footbridges that traversed the central stream in Lutyens’ walled garden 1998.

Figure 18: — Doorway in Lutyens’ dilapidated walled garden 1998.